Johnny Coley - Mister Sweet Whisper

Transcendental poetry meets Southern Nightmare Jazz on the third album by Alabama-based poet & artist Johnny Coley, collaborating here with Worst Spills.

Tapping into French surrealism and transgressive American poets such as John Ashbery, the songs in Mister Sweet Whisper evolve, cinema-like, with Coley as an uninhibited, almost mystical, narrator. Textural, noirish playing complements Coley’s decadent landscapes, which glide by like cigarette smoke invocations. Echoing, and at times, dissonant notes of saxophone, crystalline tones of vibraphone, and jagged guitar arrangements punctuate Coley’s dreamlike visions, populated by ballet dancers, haunting nightclubs, and ghostly car drivers.

Wistful and expansive, the songs in Mister Sweet Whisper speak of Coley’s talent and natural ability to channel his poetic world into songs. A remarkable follow-up to Coley’s first two albums—Antique Sadness, from 2021, and Landscape Man, from 2022—which were praised as “exquisitely haunting, sublime, hilarious” and falling “somewhere between Robert Ashley, David Wojnarowicz, and Intersystems,” Mister Sweet Whisper arrives in full form: unpredictable and brilliant.

On this Mississippi Records/Sweet Wreath co-release, Coley takes a completely improvised and semi-hallucinatory journey down decrepit southern trucking routes, gaslit Victorian alleys, past “a small frame house / transparent with fire,” and by women arguing on the cobblestones outside a dark club in Rome (“you could only see their lips”). It’s a world of flesh vehicles, supernatural waiters, and a poet trying to hitch a ride from a Chattanooga Dunkin’ at 2 am, headed south.

There’s humor and sadness in Johnny’s thick drawling voice and laconic style - warped front porch yarns made up on the spot, whispered close to the mic. Always on the outside, even when he’s the one telling the story, Coley melds the hyper-specifics of a life lived on the road with a deep, dark pool of American collective imagery. These are dreams within dreams, waves of darkness, wisdom, and plain spoken Southern humor from a brilliant, overlooked artist. “When the God of Fire / comes looking for fire / that’s a bad sign.”

It’s even more remarkable that these dense, continually unfolding stories are improvised from within Johnny’s apartment in Highland Towers, Birmingham, where health issues have kept him mostly homebound. There, a crew of young musicians around the Sweat Wreath label have lifted him up as their poet laureate, visiting him regularly and putting his poems to music. On Mister Sweet Whisper, they back him on guitar, upright bass, vibraphone, and wobbly saxes and organs. But Johnny is the star of this multi-generational cosmic lounge act, building entire universes within a song.

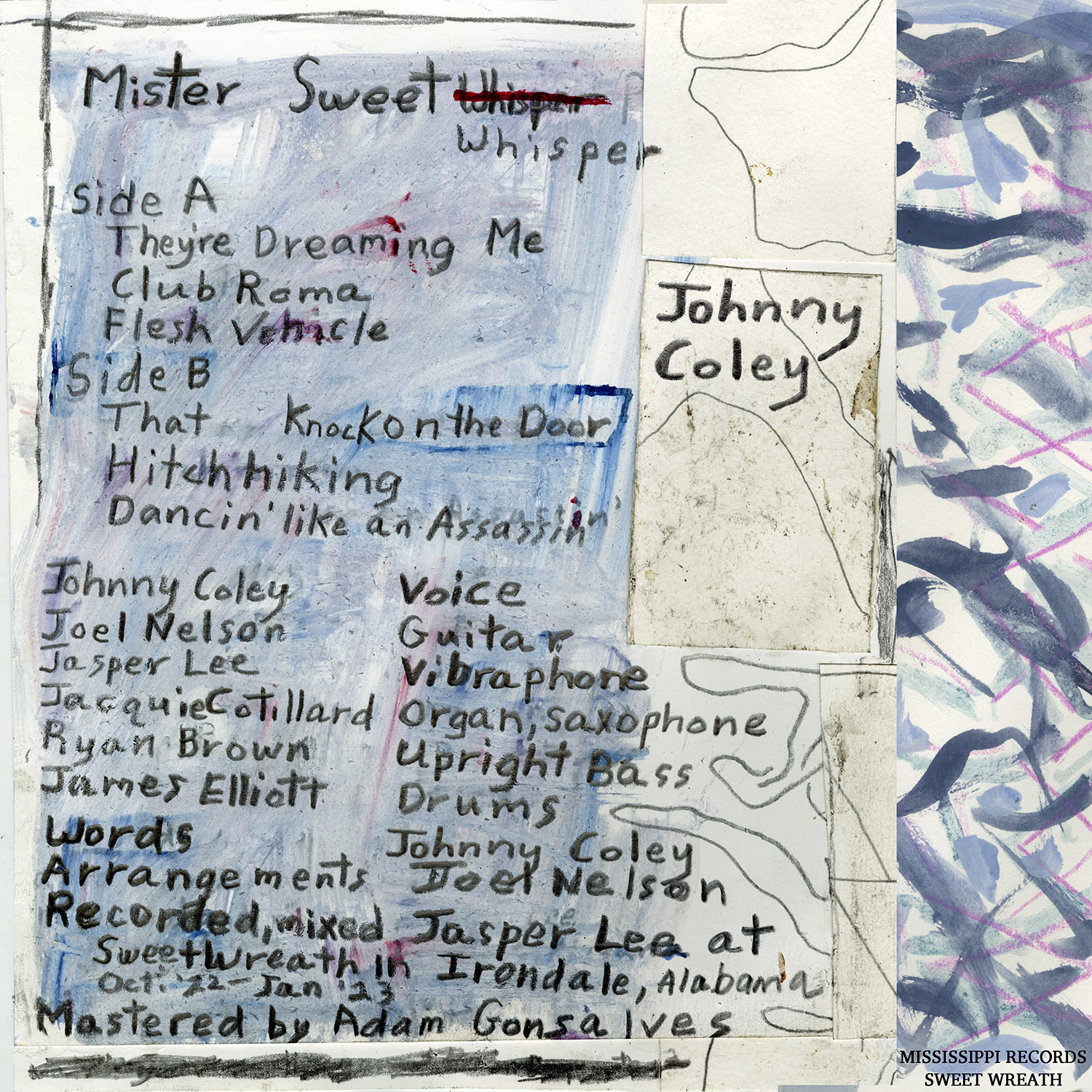

LP comes with a 4-page booklet featuring artwork by Johnny and full liner notes.

__________________________________________________________

"There is a transcendental shimmer to his plainspoken lyrics, which Coley improvises and delivers in a slow, thick drawl, whispering close to the mic. His stories unfold along interstate highways, dark alleyways, wild nightclubs, or inside a Chattanooga Dunkin’ Donuts at 2 a.m., told from the perspective of a man just passing through...We are in the unknown country of the imagination, where neither the limits of the body, nor the strictures that define America as much as any bright vision of freedom, are a match for the forces of the sublime, the ribald, and the reckless. But there is sad, sardonic wisdom in a song like “That Knock at the Door” which might apply to any number of current tragicomic spectacles. “You see the god of fire seeking fire/That’s a bad sign,” Coley growls over soft strokes of vibraphone, the faintest brush of cymbals. “And yet there’s hardly a household in this realm that hasn’t heard that knock on the door.” From a distance he watches this fallen god in simple clothes—just another person now, not unlike himself—and bows his head in sympathy, or shame..."

-Meaghan Garvey, Pitchfork, November 2024

“It’s a vision of an America turned inside out, but against all odds, Coley’s world is not unpleasant or pessimistic: there is a vibrancy and a joie de vivre which belies his world-weary delivery....We often talk about songwriters being ‘the poet of this’ or ‘the laureate of that’, but Coley is a genuine poet, someone with things to say that haven’t been said before. With Mister Sweet Whisper, he has created a document of a crazy, frayed civilization and has made it sound beautiful.“

-KLOF Magazine, November 2024

_____________________________

Interview by Maria Barrios for the Mississippi Records Newsletter:

What brought you all together for this project? When did it start? When and where did the Mister Sweet Whisper recording take place?

Joel Nelson: Worst Spills started out as a drawing board for musical ideas back in 2018. It was kind of a house band that could go in any direction. We have tried ideas that range from asking the question what kind of music would the characters from Harmony Korine’s Trash Humpers make to taking influences from the Bay Area grindcore scene and mixing that with what we have coined “Nightmare Jazz”. The Mister Sweet Whisper record came about on a single fall day in October. We recorded the music at Sweet Wreath headquarters and then recorded Johnny’s spoken word at his apartment.

Jacquie Cotillard: As one of Joel’s cadre of infiltrators, we take the call to gather pretty seriously. We get there and get our heads around the weird figures and arcane instructions, trusting that what we produce is already imbued with the character that’ll be coming through. We group-remember our identity as bones, forget how to see anything, and start grasping at the long and short curving shapes we feel of ourselves in the dark. Then Joel and Jasper take up what is left behind ringing and cut it into the precise thing we formed. We go back to having no identity together, being friends, living. I met Joel in an art-school field, Ryan on a school art-field, James among my un-art-schooling, and Jasper as a field of art. I’m deeply indebted to these men for their friendship, patience, and their relentless creativity.

Ryan Brown: Joel & Jacquie said it best, but here's some way-back context for y'all: We all really converged around the Montevallo, Alabama free-improv/avant garde scene in the 2010's! Jacquie & I met in high school & had a classic rock band(!!) and we both somehow got entwined in the really hip stuff that was going on in this remote college town down the road. Jacquie was onto that stuff very early on & showed me bands like The Residents and Zappa's more “out” records when we were in high school. Jacquie would do cut-ups of books to make poems & lyrics and other really neat John Cage-y things, often to do with composition based on chance or other forces outside oneself. I wish I could remember everything; maybe there are some old notebooks somewhere. They went pretty far out!!

So naturally when we found the Montevallo scene we & Jacquie especially were thrilled to meet other people with similar interests in small-town Alabama. There were plenty of great shows around Montevallo featuring completely improv-based bands like Flusnoix, and Jacquie & Joel were, of course, composing & playing lots of wild stuff with plenty of different groups, sometimes two or three in one night. James & I would play with their bands & others, often at Eclipse Coffee & Books. I remember big house parties with everything you'd expect from a college late-night, except instead of a Lynyrd Skynyrd cover band or a bad DJ, the centerpiece was a full bill of bands playing very loud, often very challenging avant-garde & noise-y music. There were costumes & theatrics. Dramatic lighting. Mics & megaphones hanging from the ceiling. Everybody loved it. It ruled. We eventually all made our ways towards Birmingham and continued playing this music; I relate the beginnings of Worst Spills to playing in some funny places. The band really started very heavy, almost like a metal band; I remember absolutely rocking several different unfinished basements. So so loud. We did some more mellow shows in a comic book store & one improvised free-for-all in What's On 2nd, a kind of upscale antique shop in Birmingham. There were maybe 8 or 9 musicians all spread out among the shelves & displays; our lines of sight were obscured so we could only see a few people at a time. Really great music that day. I remember that one often. I think we made our first record in December of 2019 and it was so much fun. This band is such a treat to play with.

What do you like about working with Johnny?

Joel: The best thing about Johnny is that he is really listening. When we start playing he always waits and takes in what the band is playing before saying a word. It is inspiring to hear Johnny translate our sounds into his language. He has a way of bringing you into a world and pushing the music into new and unexpected places.

James: I just love hearing him speak. His unique Southern accent, the cadence of his delivery. His voice is so captivating and hypnotic…it’s really like another instrument in the ensemble.

Jacquie: Johnny has the indelible talent for deep listening. He waits, he can lurk in words while staying in place. It’s the kind of waiting chronic pain brings, a creative spring that bubbles from underground. It’s a sardonic empathy that is so piercing and warm, totally surprising and just as you find it. In a local record store I flipped to random pages of his new novel Huron, and every word was unmistakably Johnny’s. It’s not style. Like deep-writers, he sees.

Ryan: What they said! He always seems to be looking ahead way farther than anyone else. It's not a strain for him. It's just where he's going. Prescient.

Can you tell me about your experiences playing with him live? How do people respond, etc?

Joel: My experience playing with Johnny live is like a frenzied call and response. We constantly inform each other about how the moment will take shape. The music informs the lyrics and the lyrics in turn informs the music as the improvisation grows into something beyond what I intended. It's like falling into a dream that you can have influence over but it constantly shifts, forcing you to adapt.

Jasper: I think people respond quickly to Johnny’s sense of humor and feel drawn in and comfortable enough to laugh, or say things back to him during the show. It’s a conversational type of atmosphere like being at a house party, regardless of where the show is taking place.

But then he’ll describe something so simple and beautiful that people start to cry…it’s a very honest and humble way of speaking he has. That’s the gift of playing music with someone that’s older and has such a deeply tuned awareness and perspective.

Jacquie: He has an effect somewhere between character actor and archetype. That voice speaks to something moving in a surreptitious lived history, something that has long been here. I like the emphasis by Jasper and Joel and Johnny on the “Southern” aspect of the work. I have hostile feelings toward the historical and present South — they appreciate (critically) the feeling of the weird, mysterious land here, of the resistance-to-evil that also lurks here like a kind beast. It’s mist on a grove with no context, gloomily alive. That makes people nervous, I think. Some folks get expectations about a voice like his, and they are all parried by the turns he takes, and who he is as a person. Spellbinding.

If you'd like to choose a track from the album and tell us about your pick, that would be great.

Jasper: “That Knock On The Door.” When we were recording the words for this in Johnny’s apartment, I asked Johnny to start whispering toward the ending. The mood of the music seemed to call for something like that….a very hushed voice. Johnny got very focused and started speaking in the lowest, most mysterious way I’d ever heard him before. What he was saying got very intense, and emotionally vulnerable but somehow also vaguely threatening. We both had headphones on, listening to the music as he spoke. It was just after dusk, everything getting darker and so completely still. Earlier in the track Johnny had said something about “that knock on the door”, and now we were toward the end of the music…he was still speaking and the anticipation in the air was just palpable. We both had our eyes closed. And then I swear to god, the most terrifying thing happened. Right in the middle of Johnny whispering these spooky, erotic, interior thoughts, someone knocks loudly on the door! And opens it and walks in! The mic volume was turned up to capture Johnny’s whisper, so this knock was a deafening thunder through our headphones. I shook, I was so startled by the knock on the door. It was his cousin James, walking in smiling and saying “hello!” I couldn’t believe the psychic force of the whole experience…Johnny predicting a knock which happened just moments later. It was really funny too….his cousin walking in on this incredibly weird thing of Johnny whispering to himself, and both he and I just sitting there with our eyes closed. Totally shaken out of our trance and looking confused while James is smiling as if to say “what the hell is going on y’all?!”

Jacquie: Just to add to Jasper’s note: I recall that while sitting, listening in that session Johnny spoke of a fire engine blazing by and the street behind us lit up with noise from a passing truck. Those sessions happened exactly right in time and place.

“Hitchhiking,” I think it was. That’s the one with the burning building, the long drive. I remember Johnny narrating (…geese?) hundreds of strapping paratroopers down from the sky while my displaced clown-self-past honked down Jasper’s hall. That is the most artful I’ve been since my last burning-building nightmare.

Any poetry/sound poetry/spoken word albums you like, and why?

Joel:

David Lynch and Angelo Badalamenti - Thought Gang

This record was a massive influence for the record. It is one of those albums that hints at many different genres while having a unique personality.

Harry Pussy - Let’s Build a Pussy. Its words, its a drone, it's a fuck you to expectations. A record that speaks to the soul of Nightmare Jazz.

Jacquie:

William Burroughs’ spoken word/music albums infected my adolescent brain before immunity had been established. Laurie Anderson’s work, transcending the need for coolness or defense against pretension. The schizoid (in) me loves the sound of disintegrating perspective. I lost a vinyl copy of “10+2: 12 American Text-Sound Pieces” in college, maybe from the psychic damage I did to my young Texan roommate with it. I hope it’s happy somewhere. The record, not the Texan.

Ryan:

Gil Scott-Heron for me :’) And honestly Jacquie's work in this realm is some of my favorite stuff, and very influential as I got to see much of it develop in real time. No kidding!! Very fortunate to know all these folks.

____________________________________

María Barrios: Johnny, I wanted to ask if you were born and raised in Alabama and if you can tell us about growing up there.

Johnny Coley: I was born in Alexander City, Alabama, which was then a town of about 20,000 people. My great-grandfather had a big cotton farm worked by enslaved African Americans. Because of the Civil War, he was kind of wiped out, but because he was a ferocious capitalist, he made another large amount of money.

My great-grandfather had set it up where my grandfather would have a drugstore and his brother would be a doctor. So what happened was the brother who was supposed to be a doctor, left Alabama, and so my grandfather did not end up in such a profitable situation. Then his wife and his four children died from the flu. So his wife and children died and the drugstore burned down, and so there he was, no family, no drugstore. He remarried, and he rebuilt his drugstore. I know this is a whole lot of detail, but it seems important to me somehow.

So my father, who was born in 1914, came into being in a situation that was kind of affected by chance, and I would not be here—in the same way, at least—if there hadn't been the flu and if there hadn't been the fire, you know? So I am from Alabama. How many letters are there in Alabama? Seven letters—four of those letters should be Black people. You know what I mean? Alabama is something that happens coming out of white supremacy, this whole situation between Black and white people, which was not chosen by Black people.

MB: In previous conversations, you mentioned going to school abroad for some time…

JC: Yes. I went to school in France for a year in 1968 which you know, was the year to be there. I was sitting on the steps of the house of the French family I lived with, and the students marched by chanting, and I just kind of got up and joined. I was marching along because I was opposed to the war in Vietnam. But when we got to the university, they had occupied these buildings, and I stayed there for a while—except I couldn't understand what they were saying. It was that kind of Marxist special language, and my French was terrible. One thing I did was I bought a huge amount of paperbacks of French classics and mailed them back here. So for years, I had all these French classic paperbacks lining my walls.

MB: Were you already writing at that time?

JC: I think it was around then that I was interested in writing. One reason I went to that school in France was because I felt very isolated. We moved from Nashville to Birmingham, and I started in a new school in the 10th grade. I did not adapt well. I hated it. I felt isolated, and so as soon as I could, I got out by going to France. I went there to escape this high school.

MB: You said that your grandfather, or your family, had very traditional ideas of who their sons were supposed to be. Did they have that line of thinking for you too?

JC: Well, my father was a professor and then head of the Humanities Department at the University of Alabama in Birmingham. He was very academic and very embedded in academia, and he, I'm sure, thought “I have a smart son, and he could be an academic,” but I didn’t do that. I didn’t do anything. I didn’t want to do anything and at a certain point, I was hospitalized for depression in a clinic in Birmingham and given electroshock therapy. That was a hugely shaping experience for me. To this day, I'm afraid of doctors. I have what I call medical trauma.

From that, the only job I had that kind of worked out for me was mowing lawns. I did that for the father of a friend of mine, a young guy—younger than me—who I was in love with. He was not in love with me, but he was unbothered by me being in love with him. Are you familiar with that kind of situation?

MB: Yes.

JC: So I mowed lawns and worked for that little company for several years. I just never had, in my whole life, a normal, secure, economic being. I had never known where my next meal was coming from, except that I was the child of the bourgeoisie. My parents would get me a meal, but in terms of being able to produce myself, I never had that.

Then, I lived in Tuscaloosa, which is a small town in Alabama. There, I started working at the Department of Pensions and Securities, the welfare department. I was a home health worker, and I would go to the houses of recipients of government aid and clean them up, clean the place up, and go and get groceries for them. I did that for 10 years, and it was very good for me—to lose that bourgeoise place.

After that, I came back to Birmingham from Tuscaloosa. I'm trying to think… I don't have a great memory. I never did, but now that I'm 74 it's even, what would you call it? It's a memory that doesn't want to hold anything captive. It wants everything to go free. So I don't remember when exactly, but I ended up working part-time at the library here. That was my last job before not being physically able to work anymore.

MB: Are there any poetry books that shaped your practice or that you kept close through the years?

JC: One of the first poetry books I bought was Some Trees by John Ashbery. I also love this French poet, Paul Éluard, who was a surrealist and involved with André Breton in Dada stuff.

Even after other writers left, Éluard remained a serious functioning member of the French Communist Party until 1956. I would say he's probably my favorite poet, and he was very important in the resistance to the Nazis in Paris. He took messages from one resistance group to another, and to do that, he rode public transportation.

I think I'm a little bit… I might start to cry. I'm moved by what I'm talking about. But almost everything we've talked about kind of makes me cry, so don't pay any attention to that. I'm actually cold as steel.

But those poems by Éluard, I like them because they're very straightforward, and he really seems to be doing what he says he wants to do, which is talking about people as very strong and able to create a world that supports human life. It doesn't divide it up and sell it like capitalism does, and so he's my favorite poet.

MB: I think your voice in Mister Sweet Whisper feels very free-flowing—it just sort of takes you. I find a parallel in what you said, about your memory not wanting to hold anything captive. I notice that in your songs, too. How do you get there?

JC: I guess I've always felt that good writing just kind of carries you along, and that it doesn't necessarily tell you to sit in seat 43 A and look to your right and see Philadelphia. It just kind of carries you along. You can be in your own little boat, and it just kind of carries you along.

I was also very influenced by people who got together in Tuscaloosa and considered themselves, at a certain point, surrealist. And they did events. I remember once going to a house that some of them lived in in Tuscaloosa. It was just full of people making noise, just hitting on the wall… That was a very influential thing to me. I’ll tell you something that means a lot to me. There’s an Italian writer. Giorgio…

MB: …Agamben.

JC: Giorgio Agamben. Oh God. I love him, I absolutely love him. If he was anywhere nearby, I would hug him. He would hate that… You could just kind of see him go “You're American.”

One thing he says is that poetry is language displayed simply as language. In other words, it's language that you could look at. You don't have to worry and go, is this a sentence? It's not like that. It's like listening to a saxophone… That's my feeling now about poetry, and it comes from this small Italian man who, if he gets wind of the fact that I want to hug him, he's going to hide.

MB: You mentioned political activism and friends who were in political groups, and you said you sort of rode along. What made you not participate more actively? What did and didn’t you enjoy from being around those people?

JC: I just came across people who seem to me to be extraordinary people who were full-on political people in a way that I wasn't. I think that one thing that held me back was this sort of genteel sense of how you behave.

I'll never forget I was involved with a guy named Steve Whitman, who's dead now, who to me, was an amazing person. At his memorial, his stepdaughter said, “My dad was a communist revolutionary who knew how to get things done in this world.” I think he was actually like that. I don't know how I became friends with him, but he was from Brooklyn and he was in Alabama teaching at the University of Alabama in Birmingham. He saw anti-racism, and anti-white supremacy, as being the most important thing white people could do politically. In terms of anti-white supremacy, and anti-racism, he saw prison work as being the most important thing. A lot of people see that now, but this was a long time ago. Not everybody saw things like that, and he did.

So one of the biggest prisons in Alabama was in Atmore, Alabama, which is very far to the south. Very, very, very far, down to the bottom of Alabama. Steve had an old Volkswagen, and he would go down there a lot, and I would ride with him. Well, this was not anything for him to have company on this six-hour ride through Alabama as someone from Brooklyn, you know?

I never minded something like being part of a picket line or anything like that. I just did not want to be involved in day-to-day organizing and meetings. I think I had probably an exaggeratedly negative picture of meetings.

MB: We talked about, politics, writing, and poets. When does music intersect, or what music do you appreciate?

JC: I remember in the 70s, the president of France said that music was an anesthetic for people now. I think that's kind of true. If you just had a little bit too much you put on, say, Bach, and there's this beautiful thing in the air, and it's it helps you, it refreshes and protects your mind to a certain degree.

It's funny, Jasper [Lee, who plays in The Sweet Whisper Band] and people like him, they can just pick up any instrument and just make sense with it. Well, I didn't have that feeling, because I grew up in a world where you took piano lessons, or you took cello and you learned how to play that instrument, and I could never play any instrument.

I think playing a musical instrument is a very sophisticated mind-body thing. And my mind-body thing is, my mind is this person who's in a car driving into Chicago, and my body is in Baton Rouge, and the connection may be totally lost.

I had forgotten about him, but I love Otis Redding. I can remember hearing “Try A Little Tenderness” on the radio in my bed, going to sleep at night, when I was a child. I don't know if you're familiar with that song, but it's so beautiful. Then The Tams, they were a band made up of men who sang in bars near Charleston, South Carolina. I found out about them because they had an album called Presenting The Tams, which I just loved. You should listen to it online. It's just wonderful.

MB: I probably took this from another music writer but, to close the interview, I want to ask what makes you happy.

JC: I think pot makes me happy. Or pot makes me available to happiness. You know what I mean? If I smoke pot, then I'm in the room where the ice cream of happiness is being served.

I would say landscape makes me happy. Rural, farm, field, trees landscape makes me happy. Finding out about some kind of left-wing victory makes me happy, and being with my family makes me happy, and my old friends a lot—it just so happens that a lot of the people I was closest to are dead, so being with the people I can still be with makes me happy.

![]()

Transcendental poetry meets Southern Nightmare Jazz on the third album by Alabama-based poet & artist Johnny Coley, collaborating here with Worst Spills.

Tapping into French surrealism and transgressive American poets such as John Ashbery, the songs in Mister Sweet Whisper evolve, cinema-like, with Coley as an uninhibited, almost mystical, narrator. Textural, noirish playing complements Coley’s decadent landscapes, which glide by like cigarette smoke invocations. Echoing, and at times, dissonant notes of saxophone, crystalline tones of vibraphone, and jagged guitar arrangements punctuate Coley’s dreamlike visions, populated by ballet dancers, haunting nightclubs, and ghostly car drivers.

Wistful and expansive, the songs in Mister Sweet Whisper speak of Coley’s talent and natural ability to channel his poetic world into songs. A remarkable follow-up to Coley’s first two albums—Antique Sadness, from 2021, and Landscape Man, from 2022—which were praised as “exquisitely haunting, sublime, hilarious” and falling “somewhere between Robert Ashley, David Wojnarowicz, and Intersystems,” Mister Sweet Whisper arrives in full form: unpredictable and brilliant.

On this Mississippi Records/Sweet Wreath co-release, Coley takes a completely improvised and semi-hallucinatory journey down decrepit southern trucking routes, gaslit Victorian alleys, past “a small frame house / transparent with fire,” and by women arguing on the cobblestones outside a dark club in Rome (“you could only see their lips”). It’s a world of flesh vehicles, supernatural waiters, and a poet trying to hitch a ride from a Chattanooga Dunkin’ at 2 am, headed south.

There’s humor and sadness in Johnny’s thick drawling voice and laconic style - warped front porch yarns made up on the spot, whispered close to the mic. Always on the outside, even when he’s the one telling the story, Coley melds the hyper-specifics of a life lived on the road with a deep, dark pool of American collective imagery. These are dreams within dreams, waves of darkness, wisdom, and plain spoken Southern humor from a brilliant, overlooked artist. “When the God of Fire / comes looking for fire / that’s a bad sign.”

It’s even more remarkable that these dense, continually unfolding stories are improvised from within Johnny’s apartment in Highland Towers, Birmingham, where health issues have kept him mostly homebound. There, a crew of young musicians around the Sweat Wreath label have lifted him up as their poet laureate, visiting him regularly and putting his poems to music. On Mister Sweet Whisper, they back him on guitar, upright bass, vibraphone, and wobbly saxes and organs. But Johnny is the star of this multi-generational cosmic lounge act, building entire universes within a song.

LP comes with a 4-page booklet featuring artwork by Johnny and full liner notes.

__________________________________________________________

"There is a transcendental shimmer to his plainspoken lyrics, which Coley improvises and delivers in a slow, thick drawl, whispering close to the mic. His stories unfold along interstate highways, dark alleyways, wild nightclubs, or inside a Chattanooga Dunkin’ Donuts at 2 a.m., told from the perspective of a man just passing through...We are in the unknown country of the imagination, where neither the limits of the body, nor the strictures that define America as much as any bright vision of freedom, are a match for the forces of the sublime, the ribald, and the reckless. But there is sad, sardonic wisdom in a song like “That Knock at the Door” which might apply to any number of current tragicomic spectacles. “You see the god of fire seeking fire/That’s a bad sign,” Coley growls over soft strokes of vibraphone, the faintest brush of cymbals. “And yet there’s hardly a household in this realm that hasn’t heard that knock on the door.” From a distance he watches this fallen god in simple clothes—just another person now, not unlike himself—and bows his head in sympathy, or shame..."

-Meaghan Garvey, Pitchfork, November 2024

“It’s a vision of an America turned inside out, but against all odds, Coley’s world is not unpleasant or pessimistic: there is a vibrancy and a joie de vivre which belies his world-weary delivery....We often talk about songwriters being ‘the poet of this’ or ‘the laureate of that’, but Coley is a genuine poet, someone with things to say that haven’t been said before. With Mister Sweet Whisper, he has created a document of a crazy, frayed civilization and has made it sound beautiful.“

-KLOF Magazine, November 2024

_____________________________

Interview by Maria Barrios for the Mississippi Records Newsletter:

What brought you all together for this project? When did it start? When and where did the Mister Sweet Whisper recording take place?

Joel Nelson: Worst Spills started out as a drawing board for musical ideas back in 2018. It was kind of a house band that could go in any direction. We have tried ideas that range from asking the question what kind of music would the characters from Harmony Korine’s Trash Humpers make to taking influences from the Bay Area grindcore scene and mixing that with what we have coined “Nightmare Jazz”. The Mister Sweet Whisper record came about on a single fall day in October. We recorded the music at Sweet Wreath headquarters and then recorded Johnny’s spoken word at his apartment.

Jacquie Cotillard: As one of Joel’s cadre of infiltrators, we take the call to gather pretty seriously. We get there and get our heads around the weird figures and arcane instructions, trusting that what we produce is already imbued with the character that’ll be coming through. We group-remember our identity as bones, forget how to see anything, and start grasping at the long and short curving shapes we feel of ourselves in the dark. Then Joel and Jasper take up what is left behind ringing and cut it into the precise thing we formed. We go back to having no identity together, being friends, living. I met Joel in an art-school field, Ryan on a school art-field, James among my un-art-schooling, and Jasper as a field of art. I’m deeply indebted to these men for their friendship, patience, and their relentless creativity.

Ryan Brown: Joel & Jacquie said it best, but here's some way-back context for y'all: We all really converged around the Montevallo, Alabama free-improv/avant garde scene in the 2010's! Jacquie & I met in high school & had a classic rock band(!!) and we both somehow got entwined in the really hip stuff that was going on in this remote college town down the road. Jacquie was onto that stuff very early on & showed me bands like The Residents and Zappa's more “out” records when we were in high school. Jacquie would do cut-ups of books to make poems & lyrics and other really neat John Cage-y things, often to do with composition based on chance or other forces outside oneself. I wish I could remember everything; maybe there are some old notebooks somewhere. They went pretty far out!!

So naturally when we found the Montevallo scene we & Jacquie especially were thrilled to meet other people with similar interests in small-town Alabama. There were plenty of great shows around Montevallo featuring completely improv-based bands like Flusnoix, and Jacquie & Joel were, of course, composing & playing lots of wild stuff with plenty of different groups, sometimes two or three in one night. James & I would play with their bands & others, often at Eclipse Coffee & Books. I remember big house parties with everything you'd expect from a college late-night, except instead of a Lynyrd Skynyrd cover band or a bad DJ, the centerpiece was a full bill of bands playing very loud, often very challenging avant-garde & noise-y music. There were costumes & theatrics. Dramatic lighting. Mics & megaphones hanging from the ceiling. Everybody loved it. It ruled. We eventually all made our ways towards Birmingham and continued playing this music; I relate the beginnings of Worst Spills to playing in some funny places. The band really started very heavy, almost like a metal band; I remember absolutely rocking several different unfinished basements. So so loud. We did some more mellow shows in a comic book store & one improvised free-for-all in What's On 2nd, a kind of upscale antique shop in Birmingham. There were maybe 8 or 9 musicians all spread out among the shelves & displays; our lines of sight were obscured so we could only see a few people at a time. Really great music that day. I remember that one often. I think we made our first record in December of 2019 and it was so much fun. This band is such a treat to play with.

What do you like about working with Johnny?

Joel: The best thing about Johnny is that he is really listening. When we start playing he always waits and takes in what the band is playing before saying a word. It is inspiring to hear Johnny translate our sounds into his language. He has a way of bringing you into a world and pushing the music into new and unexpected places.

James: I just love hearing him speak. His unique Southern accent, the cadence of his delivery. His voice is so captivating and hypnotic…it’s really like another instrument in the ensemble.

Jacquie: Johnny has the indelible talent for deep listening. He waits, he can lurk in words while staying in place. It’s the kind of waiting chronic pain brings, a creative spring that bubbles from underground. It’s a sardonic empathy that is so piercing and warm, totally surprising and just as you find it. In a local record store I flipped to random pages of his new novel Huron, and every word was unmistakably Johnny’s. It’s not style. Like deep-writers, he sees.

Ryan: What they said! He always seems to be looking ahead way farther than anyone else. It's not a strain for him. It's just where he's going. Prescient.

Can you tell me about your experiences playing with him live? How do people respond, etc?

Joel: My experience playing with Johnny live is like a frenzied call and response. We constantly inform each other about how the moment will take shape. The music informs the lyrics and the lyrics in turn informs the music as the improvisation grows into something beyond what I intended. It's like falling into a dream that you can have influence over but it constantly shifts, forcing you to adapt.

Jasper: I think people respond quickly to Johnny’s sense of humor and feel drawn in and comfortable enough to laugh, or say things back to him during the show. It’s a conversational type of atmosphere like being at a house party, regardless of where the show is taking place.

But then he’ll describe something so simple and beautiful that people start to cry…it’s a very honest and humble way of speaking he has. That’s the gift of playing music with someone that’s older and has such a deeply tuned awareness and perspective.

Jacquie: He has an effect somewhere between character actor and archetype. That voice speaks to something moving in a surreptitious lived history, something that has long been here. I like the emphasis by Jasper and Joel and Johnny on the “Southern” aspect of the work. I have hostile feelings toward the historical and present South — they appreciate (critically) the feeling of the weird, mysterious land here, of the resistance-to-evil that also lurks here like a kind beast. It’s mist on a grove with no context, gloomily alive. That makes people nervous, I think. Some folks get expectations about a voice like his, and they are all parried by the turns he takes, and who he is as a person. Spellbinding.

If you'd like to choose a track from the album and tell us about your pick, that would be great.

Jasper: “That Knock On The Door.” When we were recording the words for this in Johnny’s apartment, I asked Johnny to start whispering toward the ending. The mood of the music seemed to call for something like that….a very hushed voice. Johnny got very focused and started speaking in the lowest, most mysterious way I’d ever heard him before. What he was saying got very intense, and emotionally vulnerable but somehow also vaguely threatening. We both had headphones on, listening to the music as he spoke. It was just after dusk, everything getting darker and so completely still. Earlier in the track Johnny had said something about “that knock on the door”, and now we were toward the end of the music…he was still speaking and the anticipation in the air was just palpable. We both had our eyes closed. And then I swear to god, the most terrifying thing happened. Right in the middle of Johnny whispering these spooky, erotic, interior thoughts, someone knocks loudly on the door! And opens it and walks in! The mic volume was turned up to capture Johnny’s whisper, so this knock was a deafening thunder through our headphones. I shook, I was so startled by the knock on the door. It was his cousin James, walking in smiling and saying “hello!” I couldn’t believe the psychic force of the whole experience…Johnny predicting a knock which happened just moments later. It was really funny too….his cousin walking in on this incredibly weird thing of Johnny whispering to himself, and both he and I just sitting there with our eyes closed. Totally shaken out of our trance and looking confused while James is smiling as if to say “what the hell is going on y’all?!”

Jacquie: Just to add to Jasper’s note: I recall that while sitting, listening in that session Johnny spoke of a fire engine blazing by and the street behind us lit up with noise from a passing truck. Those sessions happened exactly right in time and place.

“Hitchhiking,” I think it was. That’s the one with the burning building, the long drive. I remember Johnny narrating (…geese?) hundreds of strapping paratroopers down from the sky while my displaced clown-self-past honked down Jasper’s hall. That is the most artful I’ve been since my last burning-building nightmare.

Any poetry/sound poetry/spoken word albums you like, and why?

Joel:

David Lynch and Angelo Badalamenti - Thought Gang

This record was a massive influence for the record. It is one of those albums that hints at many different genres while having a unique personality.

Harry Pussy - Let’s Build a Pussy. Its words, its a drone, it's a fuck you to expectations. A record that speaks to the soul of Nightmare Jazz.

Jacquie:

William Burroughs’ spoken word/music albums infected my adolescent brain before immunity had been established. Laurie Anderson’s work, transcending the need for coolness or defense against pretension. The schizoid (in) me loves the sound of disintegrating perspective. I lost a vinyl copy of “10+2: 12 American Text-Sound Pieces” in college, maybe from the psychic damage I did to my young Texan roommate with it. I hope it’s happy somewhere. The record, not the Texan.

Ryan:

Gil Scott-Heron for me :’) And honestly Jacquie's work in this realm is some of my favorite stuff, and very influential as I got to see much of it develop in real time. No kidding!! Very fortunate to know all these folks.

____________________________________

María Barrios: Johnny, I wanted to ask if you were born and raised in Alabama and if you can tell us about growing up there.

Johnny Coley: I was born in Alexander City, Alabama, which was then a town of about 20,000 people. My great-grandfather had a big cotton farm worked by enslaved African Americans. Because of the Civil War, he was kind of wiped out, but because he was a ferocious capitalist, he made another large amount of money.

My great-grandfather had set it up where my grandfather would have a drugstore and his brother would be a doctor. So what happened was the brother who was supposed to be a doctor, left Alabama, and so my grandfather did not end up in such a profitable situation. Then his wife and his four children died from the flu. So his wife and children died and the drugstore burned down, and so there he was, no family, no drugstore. He remarried, and he rebuilt his drugstore. I know this is a whole lot of detail, but it seems important to me somehow.

So my father, who was born in 1914, came into being in a situation that was kind of affected by chance, and I would not be here—in the same way, at least—if there hadn't been the flu and if there hadn't been the fire, you know? So I am from Alabama. How many letters are there in Alabama? Seven letters—four of those letters should be Black people. You know what I mean? Alabama is something that happens coming out of white supremacy, this whole situation between Black and white people, which was not chosen by Black people.

MB: In previous conversations, you mentioned going to school abroad for some time…

JC: Yes. I went to school in France for a year in 1968 which you know, was the year to be there. I was sitting on the steps of the house of the French family I lived with, and the students marched by chanting, and I just kind of got up and joined. I was marching along because I was opposed to the war in Vietnam. But when we got to the university, they had occupied these buildings, and I stayed there for a while—except I couldn't understand what they were saying. It was that kind of Marxist special language, and my French was terrible. One thing I did was I bought a huge amount of paperbacks of French classics and mailed them back here. So for years, I had all these French classic paperbacks lining my walls.

MB: Were you already writing at that time?

JC: I think it was around then that I was interested in writing. One reason I went to that school in France was because I felt very isolated. We moved from Nashville to Birmingham, and I started in a new school in the 10th grade. I did not adapt well. I hated it. I felt isolated, and so as soon as I could, I got out by going to France. I went there to escape this high school.

MB: You said that your grandfather, or your family, had very traditional ideas of who their sons were supposed to be. Did they have that line of thinking for you too?

JC: Well, my father was a professor and then head of the Humanities Department at the University of Alabama in Birmingham. He was very academic and very embedded in academia, and he, I'm sure, thought “I have a smart son, and he could be an academic,” but I didn’t do that. I didn’t do anything. I didn’t want to do anything and at a certain point, I was hospitalized for depression in a clinic in Birmingham and given electroshock therapy. That was a hugely shaping experience for me. To this day, I'm afraid of doctors. I have what I call medical trauma.

From that, the only job I had that kind of worked out for me was mowing lawns. I did that for the father of a friend of mine, a young guy—younger than me—who I was in love with. He was not in love with me, but he was unbothered by me being in love with him. Are you familiar with that kind of situation?

MB: Yes.

JC: So I mowed lawns and worked for that little company for several years. I just never had, in my whole life, a normal, secure, economic being. I had never known where my next meal was coming from, except that I was the child of the bourgeoisie. My parents would get me a meal, but in terms of being able to produce myself, I never had that.

Then, I lived in Tuscaloosa, which is a small town in Alabama. There, I started working at the Department of Pensions and Securities, the welfare department. I was a home health worker, and I would go to the houses of recipients of government aid and clean them up, clean the place up, and go and get groceries for them. I did that for 10 years, and it was very good for me—to lose that bourgeoise place.

After that, I came back to Birmingham from Tuscaloosa. I'm trying to think… I don't have a great memory. I never did, but now that I'm 74 it's even, what would you call it? It's a memory that doesn't want to hold anything captive. It wants everything to go free. So I don't remember when exactly, but I ended up working part-time at the library here. That was my last job before not being physically able to work anymore.

MB: Are there any poetry books that shaped your practice or that you kept close through the years?

JC: One of the first poetry books I bought was Some Trees by John Ashbery. I also love this French poet, Paul Éluard, who was a surrealist and involved with André Breton in Dada stuff.

Even after other writers left, Éluard remained a serious functioning member of the French Communist Party until 1956. I would say he's probably my favorite poet, and he was very important in the resistance to the Nazis in Paris. He took messages from one resistance group to another, and to do that, he rode public transportation.

I think I'm a little bit… I might start to cry. I'm moved by what I'm talking about. But almost everything we've talked about kind of makes me cry, so don't pay any attention to that. I'm actually cold as steel.

But those poems by Éluard, I like them because they're very straightforward, and he really seems to be doing what he says he wants to do, which is talking about people as very strong and able to create a world that supports human life. It doesn't divide it up and sell it like capitalism does, and so he's my favorite poet.

MB: I think your voice in Mister Sweet Whisper feels very free-flowing—it just sort of takes you. I find a parallel in what you said, about your memory not wanting to hold anything captive. I notice that in your songs, too. How do you get there?

JC: I guess I've always felt that good writing just kind of carries you along, and that it doesn't necessarily tell you to sit in seat 43 A and look to your right and see Philadelphia. It just kind of carries you along. You can be in your own little boat, and it just kind of carries you along.

I was also very influenced by people who got together in Tuscaloosa and considered themselves, at a certain point, surrealist. And they did events. I remember once going to a house that some of them lived in in Tuscaloosa. It was just full of people making noise, just hitting on the wall… That was a very influential thing to me. I’ll tell you something that means a lot to me. There’s an Italian writer. Giorgio…

MB: …Agamben.

JC: Giorgio Agamben. Oh God. I love him, I absolutely love him. If he was anywhere nearby, I would hug him. He would hate that… You could just kind of see him go “You're American.”

One thing he says is that poetry is language displayed simply as language. In other words, it's language that you could look at. You don't have to worry and go, is this a sentence? It's not like that. It's like listening to a saxophone… That's my feeling now about poetry, and it comes from this small Italian man who, if he gets wind of the fact that I want to hug him, he's going to hide.

MB: You mentioned political activism and friends who were in political groups, and you said you sort of rode along. What made you not participate more actively? What did and didn’t you enjoy from being around those people?

JC: I just came across people who seem to me to be extraordinary people who were full-on political people in a way that I wasn't. I think that one thing that held me back was this sort of genteel sense of how you behave.

I'll never forget I was involved with a guy named Steve Whitman, who's dead now, who to me, was an amazing person. At his memorial, his stepdaughter said, “My dad was a communist revolutionary who knew how to get things done in this world.” I think he was actually like that. I don't know how I became friends with him, but he was from Brooklyn and he was in Alabama teaching at the University of Alabama in Birmingham. He saw anti-racism, and anti-white supremacy, as being the most important thing white people could do politically. In terms of anti-white supremacy, and anti-racism, he saw prison work as being the most important thing. A lot of people see that now, but this was a long time ago. Not everybody saw things like that, and he did.

So one of the biggest prisons in Alabama was in Atmore, Alabama, which is very far to the south. Very, very, very far, down to the bottom of Alabama. Steve had an old Volkswagen, and he would go down there a lot, and I would ride with him. Well, this was not anything for him to have company on this six-hour ride through Alabama as someone from Brooklyn, you know?

I never minded something like being part of a picket line or anything like that. I just did not want to be involved in day-to-day organizing and meetings. I think I had probably an exaggeratedly negative picture of meetings.

MB: We talked about, politics, writing, and poets. When does music intersect, or what music do you appreciate?

JC: I remember in the 70s, the president of France said that music was an anesthetic for people now. I think that's kind of true. If you just had a little bit too much you put on, say, Bach, and there's this beautiful thing in the air, and it's it helps you, it refreshes and protects your mind to a certain degree.

It's funny, Jasper [Lee, who plays in The Sweet Whisper Band] and people like him, they can just pick up any instrument and just make sense with it. Well, I didn't have that feeling, because I grew up in a world where you took piano lessons, or you took cello and you learned how to play that instrument, and I could never play any instrument.

I think playing a musical instrument is a very sophisticated mind-body thing. And my mind-body thing is, my mind is this person who's in a car driving into Chicago, and my body is in Baton Rouge, and the connection may be totally lost.

I had forgotten about him, but I love Otis Redding. I can remember hearing “Try A Little Tenderness” on the radio in my bed, going to sleep at night, when I was a child. I don't know if you're familiar with that song, but it's so beautiful. Then The Tams, they were a band made up of men who sang in bars near Charleston, South Carolina. I found out about them because they had an album called Presenting The Tams, which I just loved. You should listen to it online. It's just wonderful.

MB: I probably took this from another music writer but, to close the interview, I want to ask what makes you happy.

JC: I think pot makes me happy. Or pot makes me available to happiness. You know what I mean? If I smoke pot, then I'm in the room where the ice cream of happiness is being served.

I would say landscape makes me happy. Rural, farm, field, trees landscape makes me happy. Finding out about some kind of left-wing victory makes me happy, and being with my family makes me happy, and my old friends a lot—it just so happens that a lot of the people I was closest to are dead, so being with the people I can still be with makes me happy.